|

| |

|

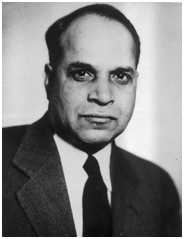

Prof. Anand N. Malaviya,

MD, FRCP (Lond.), ACR 'Master', FACP, FICP, FAMS, FNASc,

(Ex-Head of the Department of Medicine, and Chief of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology Services,

All-India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi)

Consultant Rheumatologist, 'A&R Clinic' and

Visiting Sr. Consultant Rheumatologist ISIC Superspeciality Hospital, New Delhi

|

When I landed in Boston in the mid-1960s, cortisone ruled the field of clinical immunology and rheumatology. Nobel Prize to Philip S. Hench (along with Edward Calvin Kendall and Tadeusz Reichstein) in 1950 for the discovery of cortisone had made a big impact on the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and other systemic immunoinflammatory diseases. The results obtained with cortisone were so impressive that nobody cared about any other drug, let alone a ‘cancer drug’ for their patients. During my early days in Boston (1964), I attended several CPCs in the famous ‘Ether Dome’ of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), where they had begun to discuss the serious adverse effects of cortisone with prolonged continuous use. That is when I heard the term ‘steroid sparing agents’; I vividly remember Prof. K. Frank Austin, the expert in Allergy and Immunology at Harvard Medical School, discussing the possibility of using some of the cancer drugs as ‘steroid sparing’ agents. I was very intrigued by this concept and wondered about the basis for it. As luck would have it, I got the chance of joining the Clinical Immunology and Autoimmune Diseases Group in New England Medical Centre, Boston headed by the legendary teacher Robert S. Schwartz. In the vibrant atmosphere of that department I got the answer to all my musings. Within the first week of my joining the department I heard the following story: One day in 1957 Prof. William Dameshek (Schwartz’s teacher) mused, “We need a better way than radiation (for the transplanted organs to survive). Maybe if we think of the immune response as a leukemic reaction with proliferating cells, we can stop it chemically.” Then he turned to Schwartz, barely thirty years old, and said, “You work on this.” Luckily for Schwartz scientists working in Burroughs-Welcome drug research company lead by George Hitchings, and his student a lady chemist Gertrude Elionwho had been working on drugs that could interrupt the cell cycle by interfering with nucleic acid synthesis.The year 1950 was a breakthrough year when Gertrude Elion created a purine chemical that disrupted the formation of leukemia cells. It was first successfully tested on animals and subsequently on humans. It brought about complete remission of leukemia. This drug was 6-mercaptopurine, or 6-MP in short. (Many years later George Hitchings and Gertrude Elion shared the 1988 Nobel Prize along with Sir James Black of London for their discovery of the antiviral drug acyclovir, and later AZT for HIV). In 1958 Elion had shown that 6-MP could also interfere with the immune system. Therefore, Schwartz got down to studying the effect of 6-MP on suppressing graft rejection in experimental models. His findings in this regard were electric. A series of papers that Schwartz and Dameshek co-authored in 1958 and 1959 showed decisively that the problem of organ rejection could be solved through a chemical damping down of the immune system at the time of transplantation. Thus Schwartz identified the best drug for surgeons to use—namely 6-Mercaptopurine (6-MP).

The discovery of chemical immunosuppression opened up the field of organ and bone marrow transplantation at a blow. By 1965 it had become clear that 6-MP (which might still be considered ‘safe’ for treating leukemia) was too toxic for immunosuppression in humans. In 1957, George Herbert Hitchings and Gertrude Elion, working at Burroughs-Welcome, had modified 6-MP and synthesized a prodrug (named BW 57-322, later named azathioprine) with a stronger immunosuppressive effect and much less toxicity. Burroughs-Welcome named the prodrug ‘Imuran’ (azathioprine), in line with ‘Myeleran’ (busulfan for myeloid leukemia) and ‘Leukeran’ (chlorambucil for lymphoid leukemia).With the availability of ‘Imuran’ we in Schwartz’s group quickly switched over to using it (in place of 6-MP) as the ‘steroid sparing drug’ in our patients that by-and-large consisted of lupus. Then, suddenly we were faced with a young boy with severe dermatomyositis who did not respond to prednisolone even at a dose of 100 mg daily. He was seriously ill with involvement of respiratory and pharyngeal muscles. He was in the ICU, on a respirator with a stomach tube for feeding. Obviously he was dying. On ward round we were discussing the possibility of adding ‘Imuran’ but that would take some time to work. Can we

Yellapraga Subbarao - Unsung Science Hero of India

Born: January 12, 1895, Bhimavaram, India

Died: August 9, 1948, New York, United States

use something that would work faster? Schwartz had been using Dr.YellaPragada Subbarao’s (See appendix - YellaPragadaSubbarao - Unsung science Hero of India*)drug amethopterin (later renamed methotrexate) in animal experiments to see if it can also modulate immune response. At the Lederle drug research company, Subbarao had developed a method to synthesize folic acid. After his work on folic acid, with considerable inputs from Dr. Sidney Farber (a Boston Pediatrician interested in the treatment of childhood leukemia), he synthesised the important

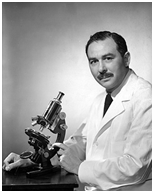

Prof. Sydney Farber, Boston

anti-cancer drug methotrexate - one of the very first cancer chemotherapy agents. Amethopterin (methotrexate) had been shown to be an effective suppressor of antibody synthesis by Friedman et al (J Exp Med 1961; 114:173) and Hersh et al (Cancer Res 1965;25:997). Observations had already been published that dermatomyositis is often associated with diseases that were thought to have immunological basis and may show autoantibodies in their blood (Keil Arch Int Med 1940;66:109; Banks NEJM 1941;225:433). Prof. Schwartz asked me ‘Anand, what would you like give to him’? I thought to myself that time was the essence. ‘Imuran’ being an oral drug may take longer to work. Moreover, it may take a few days to get the drug. On the other hand, amethopterin (methotrexate) could be given intravenously and it was available on the shelf of our laboratory for use in animal experiments. I responded “I would like to give methotrexate intravenously; that would save time”. The whole team agreed. The question was about the dose. The group’s consensus was to use a ‘small dose’ of only 100 mg IV bolus (as against the dose Prof.Sydney Farber used for leukemia, which was in grams). I rushed to the laboratory, got the methotrexate vial and administered it to the dying boy right away. As they say, the rest is history! The boy responded dramatically with return of swallowing reflex and normal breathing. Within a few days he regained muscle strength to a degree that he was discharged with advice on regular doses and follow-up. This patient and luckily, the 3 subsequent patients also showed a similar striking response. The details of these cases can be found in our original paper (Malaviya, Many, Schwartz Lancet 1968; 2: 485-88)

New Eng Med Ctr Clinical Immunology - Haematology Group (1966); Malaviya (red arrow); Prof. Schwartz (White arrow)

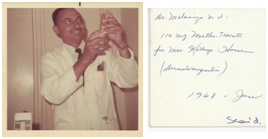

(Anand Malaviya giving 100 mg IV MTX to one of the 4 earliest patients - New England Medical Centre, Boston; June 1968).

What was our feeling on seeing this dramatic response? Simply ecstasy! Prof. Schwartz immediately got down to writing a paper on this ‘discovery’. It also taught me that you should never let your efforts go in vain. Instead collect relevant information accurately and immediately write a paper. This is what counts in science in the long-run.

|

|

Let me first define‘ high dose methotrexate (HD-MTX)’ and low-dose methotrexate (LD-MTX). I recommend my rheumatology colleagues to take a look at the review article by Cronstein on this topic [Cronstein BN. Low-Dose Methotrexate: A Mainstay in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Pharmacol Rev 57:163–172, 2005]. Cronstein writes “As an antirheumatic agent, methotrexate is administered intermittently (weekly) in doses two or three log orders lower than those required for the treatment of malignancy (5–25 mg/week versus 5000 mg/week)”.This should allay the fear among rheumatologists and patients with immunoinflammatory rheumatic diseases that MTX, a cancer drug, is being prescribed for a non-malignant disease. As we explained in great detail in one of our not-so-recent paper, for all practical purposes LD-MTX and HD-MTX for clinical use are 2 different drugs [Malaviya AN, Sharma A, Agarwal D, Kapoor S, Garg S, Sawhney S. Low-dose and high-dose methotrexate are two different drugs in practical terms. Int J Rheum Dis 2010; 13:288-293.].This is akin to the case of Low Dose-aspirin vs High Dose-aspirin. HD-aspirin is given for its anti-inflammatory, antipyretic and analgesic properties at the dose of 1 to 6 gm/day. In contrast, LD-aspirin is an anti-platelet agent commonly used at the dose of 75 or 150 mg/day. For the sake of brevity, I shall only summarise the mechanism of action of HD-MTX in the following manner: MTX (high dose) competitively inhibits (1000-fold higher affinity than folate) dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), an enzyme that catalyzes tetrahydrofolate synthesis (displacing the binding of folic acid). Consequently, folate binding is suppressed leading to suppression of the de novo synthesis of nucleoside thymidine, required for DNA synthesis. Folate is also required for purine and pyrimidine base biosynthesis. In this manner, HD-MTX inhibits DNA synthesis and the cell dies (cytotoxic).In summary, HD-MTX for cancer treatment -> high dose in grams -> suppression of DNA synthesis -> cell death -> CYTOTOXIC. Thus HD-MTX disrupts the cell cycle by inhibiting purine-pyrimidine synthesis by competitively inhibiting folate metabolism and causing cytotoxicity. This effect is obviously more pronounced on rapidly dividing cells e.g. leukemic cells, bone marrow cells, epithelial lining cells in the gut.

In contrast, LD-MTX that is used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other immunoinflammatory rheumatic diseases does NOT inhibit the DHFR enzyme involved in folate metabolism. Therefore, LD-MTX does NOT cause CYTOTOXICITY. Although the exact mechanism of action of LD-MTX is becoming clear only in recent days, it can be stated that LD-MTX acts as an anti-inflammatory drug but unlike non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, it mimics the action of glucocorticoids and thus act as a ‘steroid sparing drug’. To be more precise, recent studies have demonstrated the following multiple of action of LD-MTX:

- inhibition of enzymes involved in purine metabolism, leading to accumulation of adenosine, an immunomodulating molecule.

- Inhibition of T cell activation

- Suppression of intercellular adhesion molecule expression by T cells

- Selective down-regulation of B cells

- Increasing CD95 sensitivity of activated T cells

- Inhibition of methyltransferase activity, leading to (de)-activation of enzyme activity relevant to immune system function

- Inhibition of binding of Interleukin-1β to its cell surface receptor

A very recent exciting work related to the mode of action of LD-MTX has been published by Cribbs et al [Cribbs AP et al. Arthritis & Rheumatology2015;67:1182–92]. Their work clearly establishes that MTX restores defective Tregcell function through demethylation of the FOXP3 locus, leading to a subsequent increase in FoxP3 and CTLA-4 expression. Thus, in summary it can be stated that LD-MTX is truly an immunomodulatory drug and NOT an immunosuppressive / cytotoxic drug.

|

|

|

There is extensive evidence and pediatric rheumatologists would vouch for it that LD-MTX is very well tolerated in children without any unusual adverse effects that are not seen in adults. Elderly persons are at a disadvantage because their body does not tolerate some of the systemic autoimmune diseases as well as a younger person’s body, for example, it is well established that elderly-onset RA has a poorer prognosis than adult RA. However, there is no definite proof that elders do not tolerate LD-MTX well; a literature search shows that low dose methotrexate treatment in elderly patients appears to be safe [Hirshberg B, et alPostgrad Med J 2000;76:787-789]. However, caution is required to ensure that renal function is not compromised due to any comorbidity. If present, LD-MTX dose would need to be adjusted accordingly.

|

|

| The answer to this question is easy. The reader can access evidence-based recommendations in this regard from some seminal papers [Visser K, et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1086-93; Visser K, van der Heijde D. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1094-9]. If there is no contraindication to MTX, the starting dose can be 15 mg weekly. I (many other top rheumatologists including Dr. Edward Keystone from Canada and several others [Hazlewood GS, et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;0:1–6.]) start with a subcutaneous injection of LD-MTX 15 mg/w for 2 weeks and subsequently escalate the dose to 20 mg/w. If a good response is not achieved in another 2 weeks, I escalate the dose to 25 mg/w. This may sound unusual but it should be understood that most RA patients present with severe disease activity and may have been on suboptimal doses of DMARDs before presenting to us rheumatologists. Of course, careful assessment to ensure safety with this dose of MTX is essential. There is no absolute total dose or time limit as regards LD-MTX therapy in rheumatological diseases. Usually once remission is achieved and sustained, most rheumatologists start to slowly taper the dose down or stretch the dose interval. However, in some exceptional cases, prolonged treatment with LD-MTX needs to be continued to maintain remission or low-disease activity. The usual maintenance dose is ~ 10 mg/week but many patients need 15 mg/w to maintain remission.

|

|

Traditionally LD-MTX has been administered in a once weekly dose. However Weinblatt and Kremer in their outstanding discussion on LD-MTX during ACR 2014 in Boston [http://www.the-rheumatologist.org/article/2014-acrarhp-annual-meeting-methotrexate-use-in-patients-with-ra/] mentioned that once stable remission is achieved, the dosing interval can be stretched to once in 2 weeks. In 1999 Luis M and his team conducted a randomized trial about the same (Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42:2160.) The trial included 51 patients who had been on MTX for at least nine months and who were in remission for at least six months. The patients were assigned to weekly or every-other-week MTX, which reduced the monthly dose by one-half. It was found that the frequency of maintenance of remission at 24 weeks was the same in the two groups (95 versus 91 percent). All the patients whose synovitis recurred during every other week therapy were controlled after resumption of weekly MTX.

While on this subject of LD-MTX dosing and scheduling I wish to bring out a crucial point. In his ACR-2014 talk, Dr. Joel Kremer had stated that exposure to a serum level of methotrexate above 0.05 µM for more than 24 hours can have cytotoxic effects on rapidly dividing cells (e.g. bone marrow, GI tract). This has important implications in dose scheduling. Thus, even if small doses are given continuously for a few days, 0.05 µM levels will be maintained for more than 24 hrs causing cytotoxicity that could be lethal. On the other hand if the dose is split and given within 24 hrs, this adverse effect can be avoided. This subject is of practical importance. It has been shown that oral dose of LD-MTX actually has only about 70% bioavailability, which further declines above the dose of 15 mg. This phenomenon is most likely due to the presence of the saturable transporter, reduced folate carrier 1 (RFC1) in the gut. Therefore, if a higher than 15 mg dose of LD-MTX is to be given, it could be split in 2 doses to be administered within 24 hrs. This is the rational of giving 10 mg or 12.5 mg after breakfast and after dinner on the same day or with dinner and after breakfast on the next morning, which ever suits the patient. Whether splitting the LD-MTX dose into 2 or 3 equal doses given 2 or 3 times per week would be effective without any unusual toxicity has not been studied yet to the best of my knowledge. I have come across prescriptions where 5 mg MTX was advised to be taken 2 or 3 times in a week. I prefer avoiding such schedules until properly designed studies yield sufficient evidence in this regard. Lastly, it may be important to know that the half-life of methotrexate in serum is in the range of 6 to 8 h after administration and that the drug is undetectable in the serum by 24 h.

|

|

| LD-MTX is so versatile that it combines very well with almost all conventional synthetic DMARDs including hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), sulfasalazine (SSZ) and leflunomide (LFN). I prefer HCQ since evidence from controlled trials has shown that it enhances the efficacy of LD-MTX. Additionally, HCQ has many other beneficial effects including anti-platelet, lipid lowering and anti-diabetic effect among several others. Considering the growing prevalence of metabolic syndrome particularly in India, I feel HCQ must always be included in any regimen for the treatment of RA and other immunoinflammatory rheumatic diseases. I consider HCQ a ‘wonder drug’. Of course the O’Dell regimen of LD-MTX with SSZ+HCQ is widely used but it increases the ‘pill burden’ which may be a deterrent to patient compliance. LD-MTX with LFN is highly effective but relatively more toxic requiring close monitoring by an experienced rheumatologist. As regards the combination of LD-MTX with biologicals, evidence from extensive trials show that the efficacy of all biologicals is enhanced when combined with LD-MTX, with one tocilizumab being the only exception. The latter has shown to be equally effective without LD-MTX. A recent trial with adalimumab has demonstrated that in this combination, even 10 mg weekly LD-MTX is adequate for achieving satisfactory result However, whether this LD-MTX dose is optimal for combinations with other biologicals is yet to be established. |

|

| MTX induced nausea is a common problem among patients receiving LD-MTX. Interestingly it becomes more prominent as the patient improves. Regular folic acid supplementation prevents MTX induced nausea to a large extent (usual dose 5 mg per week on the next day after the LD-MTX dose; also prevents liver and bone marrow toxicity; should be always prescribed with LD-MTX). Most experts believe that over a period of time MTX induced nausea wanes off naturally. But, there is the danger that the patient may discontinue treatment before achieving remission or a low-disease state. Therefore, it must be explained to the patient is that MTX induced nausea though bothersome is NOT a lethal adverse effect. Reassuring the patient about this usually goes a long way in helping him/her tide over this problem. Additionally, the patient can be prescribed an anti-emetic commonly used in clinical practice e.g. ondansetron, granisetron or the more recently introduced palonosetron to help reduce MTX induced nausea. The antiemetic is generally given an hour before the LD-MTX dose and repeated after 12 (and if required) after 24 hrs. Interestingly, Kremer mentioned in his ACR-2014 talk that a cup or 2 of coffee before LD-MTX dose also helps relieve ‘methotrexate blahhh…’. However, I must admit that I have faced some rare cases (not more than once in 5-10 years - not evidence-based!) wherein no treatment works and the patient has to be switched over to some other DMARD(s) |

|

|

This is a very interesting question. I always thought that MTX nodulosis is uncommon. But after reading several papers on the subject I also started to note its appearance especially when the patient was otherwise in remission. However, one can never be sure if MTX nodulosis is not due to RA itself unless a drug withdrawal experiment is done. Because there are reports of the disappearance of MTX nodulosis while continuing with MTX therapy, I reassure the patients and do not discontinue the drug. |

|

| Fortunately, I have never seen any patient with MTX pneumonitis. But, it is possible that such a patient may have never returned to me and may have consulted some other doctor for treatment. In their 2 recent papers, Conway and colleagues from Ireland reviewed 7 major publications from 1995 to 2014 that reported respiratory adverse effects of MTX [Conway R, Low C, Coughlan RJ, O’Donnell MJ, Carey JJ. Methotrexate and lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:803–12; BMJ 2015;350:h1269]. They found only 1 patient with MTX-pneumonitis but no details of how the diagnosis was established. On searching the available literature for MTX-pneumonitis, I found several articles with contradictory reports [ClinRheumatol 1997;16:296; Arthritis &Rheumtol 1997;40:1829; ClinRheumatol 1997;16:296; J Rheumatol 1995;22:1043; Ann Rheum Dis1994;53:434]. These papers reported pneumonitis ranging from 0.3 to 18% with a mean of 3.3%. A relatively more recent paper cited the incidence o pneumonitis to be only 1 in 108 patient-years compared with 1 in 35 patient-years for hepatic toxicity and 1 in 58 patient-years for neutropenia [Grove ML, Hassell AB, Hay EM, Shadforth MF. Adverse reactions to disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in clinical practice. Q J Med 2001;94:309–19].Interestingly, the criteria for the diagnosis of MTX-pneumonitis were proposed in 1987 [Searles G, McKendry RJ. J Rheumatol 1987;14:1164–71]. These criteria are: 1. Acute onset dyspnea; 2. Fever >38.0°C; 3. Tachypnea 28/min and dry cough; 4. Radiological evidence of pulmonary interstitial or alveolar infiltrates; 5. White blood cell count >15.0 x 109/l with or without eosinophilia; 6. Negative blood and sputum cultures (mandatory); 7. Restrictive defect and decreased diffusion capacity on pulmonary function tests; 8.PO2<7.5 kPa on normal room air; 9.Histopathology consistent with bronchiolitis or interstitial pneumonitis with giant cells and without evidence of infection. Definite MTX pneumonitis is diagnosed in the presence of 6 of the above criteria; probable disease with 5 criteria and possible diseasewith 4 of the criteria. After going through the available literature I am of the opinion that MTX-pneumonitis must be a rare complication of MTX therapy. As regards the management of MTX-pneumonitis, Saravanan and Kelly have suggested the following [Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004; 43: 143-147]: Patients with no obvious signs of a chest infection may have to be hospitalized. MTX must be discontinued immediately. Discontinuation alone may be sufficient to bring about improvement. Oral or intravenous pulse glucocorticoids may be required in more serious cases. Hypoxia may require ventilation. Cyclophosphamide has been used successfully to treat more serious cases with significant pneumonitis [Suwa A, et al.ClinExpRheumatol 1999;17:355–8]. As I have not come across any case with MTX pneumonitis, I cannot answer the question on re-challenge. Common sense dictates that re-challenge should be avoided because it may have serious consequences in some patients. |

|

| Yes, I am aware of the ‘severe aversion’ to methotrexate among most physicians and especially among pulmonologists. For most of them, irrespective of the dose, duration, underlying lung comorbidity, smoking etc., MTX is always ‘the culprit’ for any lung disease! Fortunately, two recent evidence-based papers by Conway et al from Ireland (mentioned above) should allay all these unfounded fears related to MTX lung toxicity, specifically ILD or lung fibrosis [Conway R, Low C, Coughlan RJ, O’Donnell MJ, Carey JJ. Methotrexate and lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheumatol2014;66:803-12; BMJ 2015;350:h1269]. Conway et al approached this issue in a novel way. They chose patients with 2 diseases, namely psoriatic arthritis and Crohn’s disease which employ LD-MTX as standard therapy. But, unlike rheumatoid arthritis, these diseases DO NOT cause lung complications. In their cleverly designed study, Conway et al showed that no lung disease was seen in these patients despite similar dose-duration of LD-MTX treatment as is given in RA. Thus, the study concluded that LD-MTX does NOT cause lung disease by itself. Therefore, in the context of RA, a disease known to cause ILD, it is likely that lung disease develops due to suboptimal treatment and uncontrolled RA disease activity. Therefore, more aggressive treatment may be necessary for controlling RA disease activity and consequently favourably impact ILD. However, several earlier studies have cautioned against the use of MTX in those with underlying lung disease (COPD, other chronic lung diseases). Therefore, it is important to screen a patient with RA for any underlying lung disease through history taking, examination and a standard chest radiograph. The patient must be counselled accordingly and especially against smoking. If these precautions are implemented, the treatment of RA with LD-MTX is unlikely to cause any lung problem. |

|

| If one considers LD-MTX an immunomodulator, then most diseases with immunoinflammation as the underlying pathogenesis would be candidates for treatment with LD-MTX. Diseases such as RA, psoriatic arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, SLE (especially with arthritic presentation), inflammatory myopathies (dermato- and polymyositis), scleroderma, relapsing polychondritis, sarcoid arthritis, arthritis in Sjögren’s syndrome and arthritis in Behcet’s disease would be candidates for treatment with LD-MTX. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and a few other forms of systemic vasculitides also respond to LD-MTX. In fact I use LD-MTX to treat all forms of inflammatory joint diseases associated with any condition, and in instances when I cannot place an inflammatory arthritis in any well-defined category. I consider LD-MTX a ‘broad-spectrum anti-autoimmune / anti-autoinflammatory drug’! |

|

| The first and foremost thing I tell them is that the drug that I am going to prescribe is called LD-MTX which has nothing to do with the drug called HD-MTX. I explain to them that because of the similarity between the names, there is a lot of confusion. I warn them against anybody misguiding them that a cancer drug has been prescribed. If they hear any such thing, they must forcefully clarify that they are confusing LD-MTX with a different drug with a similar-sounding name. The second thing I carefully explain to them is the dosage and importance of strict adherence to a weekly schedule. If by mistake the patient takes LD-MTX daily for some time, she/he should immediately discontinue it and consult the treating rheumatologist. I also advise them about moderation in alcohol (a maximum of one drink per day) and not to take it 24 hours either side of the LD-MTX intake. I warn them against taking co-trimoxazole or any other sulfamethoxazole-containing drug. I explain to them that painkillers do NOT go well with LD-MTX because the combination causes increased liver toxicity. Therefore, these drugs should be taken only after consulting the rheumatologist. In a rare situation, if the patient requires hemodialysis LD-MTX must be discontinued in advance. This is because MTX is not dialyzable; it would quickly build up in the body reaching toxic levels. Of course, any known liver disease (chronic hepatitis etc.) or renal disease may be a relative contraindication to LD-MTX. |

|

| I strongly advise all reproductive age women to use a fool proof contraception method after consulting their obstetrician while on LD-MTX therapy. I also tell them to seek advice from me before planning a baby. I ask them to give me a 2-3 month notice (actually the duration over 2 menstrual cycles) if they are planning for a baby. Discontinuing LD-MTX over a period covering the next 2 menstrual cycles renders the body safe for pregnancy. However, if the woman has not been carful and gets pregnant while taking LD-MTX, it becomes a medico-legal issue. Therefore, I advise pregnancy termination in such cases. If they decide to overlook my advice and continue the pregnancy, then that would be their choice and responsibility (in case congenital malformations occur in the baby). Males taking LD-MTX have no such concerns to consider; they can father a child without having to discontinue the drug. |

|

| I guess I have been lucky. I have not seen a single case with this condition among my patients. If this has occurred, they have not returned to me. |

|

| There are no biomarkers in RA for predicting response to LD-MTX. Several genetic markers and non-genetic factors are under study. It is hoped that these would be available to us in the near future to guide us in the treatment of RA with more certainty of response. |

|

|

|

|

|

|