|

I would begin this section by first discussing a few index cases and then the topic.

Case 1

A 50-year-old man presented with pain in the left lumbar region, abdomen, and front of leg for the last 1 month. His pain increased on sitting cross-legged and walking but decreased on bending forward. He also had high-grade fever for the past 10 days. He had a history of Koch spine that was treated with decompression and debridement 10 years back. He also was on therapy for diabetes mellitus and ischemic heart disease.

On examination, the left hip was in flexion and external rotation. There was a tender swelling in the left flank. The psoas sign was present, but there was no significant thigh and knee joint abnormality. Additionally, the contralateral hip joint and findings of systemic examination were normal.

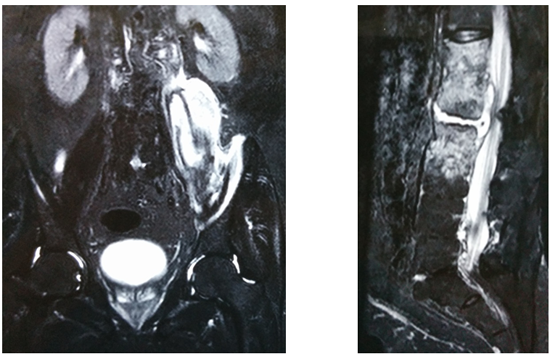

Investigations: Hemoglobin, 7 g/dL; WBC count, 12,000/µL (neutrophils 89%); erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), 50 mm/h; serum creatinine, 3.2 mg/dL; serum bilirubin, 4.2 mg/dL; hepatitis E antigen, positive; 2D echocardiography, 40% ejection fraction with basal hypokinesia; X-ray of lumbosacral spine showed reduced disc space between the 12th dorsal and 1st lumbar vertebrae and also the 3rd and 4th lumbar vertebrae with increased diameter of psoas shadow seen on the left side; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a collection of approximately 15×6.6 cm in the left psoas muscle extending to the left iliacus muscle, epidural collection at the L1 vertebra compressing the thecal sac, and marrow hyperintense signal from T12 to S1 vertebrae with destruction of intervening disc space between T12–L1 and L3–L4 vertebrae (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Magnetic resonance imaging scans showing iliopsoas abscess with lumbar vertebrae involvement.

Treatment and course in the hospital: Ultrasonography (USG)-guided aspiration was done and the abscess was drained. In view of the medical history, empirical antitubercular therapy was initiated. However, the patient’s condition continued to deteriorate clinically. Repeat MRI scan revealed an increase in the size of abscess, and surgical incision and drainage were repeated. Cultures showed growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antitubercular therapy was stopped and ciprofloxacin 750 mg was initiated and continued for 6 weeks. He showed clinical, hematologic, and radiologic improvement. There was no recurrence of infection.

Case 2

A 31-year-old man presented with pain in the abdomen for the past 1.5 months and a high-grade fever for past 10 days. Renal calculus was diagnosed and appropriate treatment was given. However, the symptoms did not resolve and MRI of the lumbar spine was done. MRI showed a right-sided iliopsoas abscess measuring 3.4×4.1×7.4 cm (see Fig. 1). Computed tomography (CT)-guided biopsy analyses identified Escherichia coli and Streptococcus spp. The patient was referred to our institute at this stage for formal open drainage of the abscess.

Fig. 1: Magnetic resonance imaging scans showing a right-sided iliopsoas abscess.

On examination, there was flexion and external rotation of the right hip. There was a tender swelling in the right iliac fossa measuring 4×5 cm. The psoas sign was present, and no significant thigh and knee joint abnormality was noted. The contralateral hip joint was normal.

Investigations: Hemoglobin, 11.8 g/dL; WBC count, 12,200/µL (neutrophils 81%); ESR, 93 mm/h; C-reactive protein, positive (192 mg/L); CT scan of the abdomen with contrast indicated a right-sided iliopsoas abscess measuring 7.8×6.1 cm along with thickening of the terminal ileum and cecum.

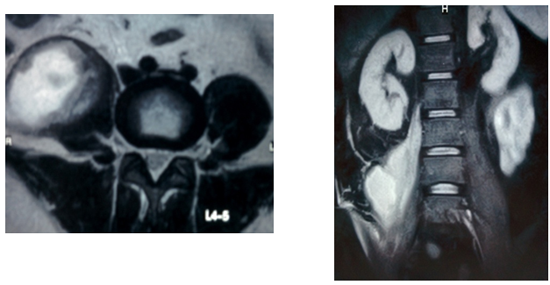

Treatment and course in the hospital: Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed, which did not reveal any intra-abdominal pathology. The abscess was drained extraperitoneally. The patient was prescribed Inj. tigecycline 50 mg every 12 hours for 6 weeks. The patient showed clinical, hematologic, and radiologic improvement (see Fig 2).

Fig. 2: Magnetic resonance imaging scans showing complete resolution of the abscess 3 months after drainage.

However, 3 months after drainage, the patient developed septic arthritis of the left hip joint. Arthrotomy and debridement was done followed by appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Case 3

An 86-year-old woman presented with severe pain in the anterior aspect of the right thigh for 2 weeks. She had been unable to walk for the past 2 weeks. There was no history of trauma, fever, significant weight loss, or loss of appetite.

On examination, there was flexion and external rotation of the right hip. There was a tender swelling of 10 × 8 cm in the right flank and the psoas sign was present. The other findings of the examination were normal.

Investigations: Hemoglobin, 8 g/dL; WBC count, 28,000/µL (neutrophils 85%); ESR, 140 mm/h; X-ray of the pelvis with bilateral hip joints, right thigh, and lumbosacral spine was normal except for the expected degenerative changes; CT scan of the abdomen showed a right-sided iliopsoas abscess measuring 16×9×9 cm, extending from the L3 vertebra up to the proximal thigh (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: CT scan showing a right-sided iliopsoas abscess.

Management: Psoas abscess drainage was done by a lateral incision above the crest of the ilium by splitting the muscles. On draining the pus, a mucinous material was coming from a small opening in a rounded structure lateral to the psoas muscle, which could not be identified. On pressing, bits of tissues were found.

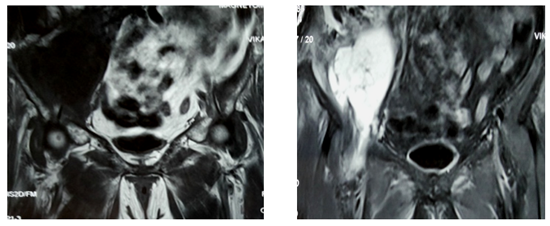

Samples of the pus and granulation tissue were sent for microbiologic and histopathologic analysis. On postoperative day 2, the right flank swelling recurred. Pain and tenderness was as severe as it was preoperatively. MRI of the abdomen showed a hypointense signal on T1-weighted images and hyperintense signal of the psoas on T2-weighted images (see Fig. 2). Surgical re-exploration was again performed in the patient.

Fig. 2: T1- and T2-weighted images showing recurrence of iliopsoas abscess.

Culture report: Polymicrobial infection with viridans group streptococci and P. aeruginosa was reported and treatment with Tab. linezolid 600 mg given

twice a day was initiated.

Histopathology: Metastasis of mucin-secreting adenocarcinoma infiltrating the muscle with a pyogenic abscess.

The CT scan of the abdomen was reviewed again. The psoas abscess was seen communicating with a tumor in the colon (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Psoas abscess communicating with a tumor in colon.

Pyogenic Iliopsoas Abscess

Introduction

Iliopsoas abscess (IPA) is a rare and potentially life-threatening suppurative myositis of the iliopsoas compartment with an incidence rate of 0.5

cases per 10,000 hospital admissions in 1993–2004 and 6.5 cases per 10,000 hospital admissions in 2005–2007 (urban tertiary care center).1

It was first described in 1881 by Mynter, who referred to it as psoitis.2

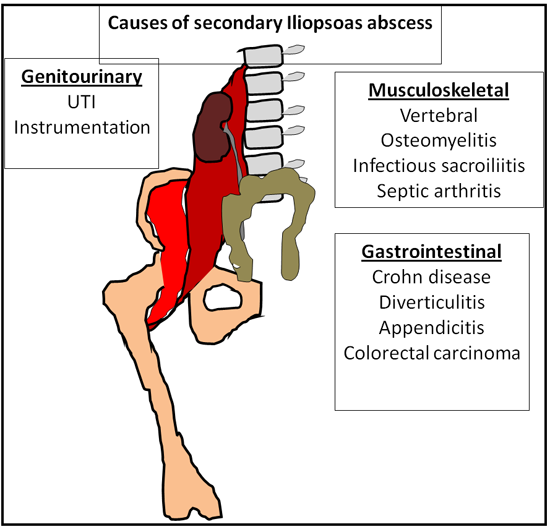

Iliopsoas abscesses may be primary (30% cases) or secondary (70% cases) in origin, depending on the presence or absence of underlying disease.

Ricci et al. found that the etiology of IPA was linked to the geographic area, with more than 90% of cases in Asia and Africa being primary

in origin while in Europe only 18.7% of reported cases were primary.3,4

The primary type is caused by hematogenous or lymphatic spread of bacteria, usually from an occult source,5 and is usually seen in immunocompromised patients

such as diabetics, alcoholics, intravenous drug abusers, human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals, patients with malignancies, or patients with

chronic illness. Staphylococcus aureus (88%) is the most common causative microorganism, followed by streptococci (5%) and E. coli (3%).4 In recent years,

MRSA has become the predominant pathogen in psoas abscesses with definitive microbiologic diagnosis, accounting for up to 25% of cases.1 The secondary

IPAs occur because of local extension of an infective process (see Fig. 1). Chronic inflammatory conditions of the digestive tract (Crohn disease [60%],

appendicitis [16%], and ulcerative colitis, diverticulitis, and colon cancer [together 11%]) are the most common causes of secondary abscess in developed

countries. Cultures are often mixed, with E. coli and Bacteroides spp. predominating. Other organisms include enteric pathogens, Staphylococcus spp.,

Enterococcus faecalis, Peptostreptococcus, and Streptococcus spp.4

The increasing incidence of tuberculosis of the spine owing to drug resistance and immunodeficiency has made it the leading cause of secondary abscesses

in the developing countries; 5% of cases of tuberculosis of the spine develop IPAs.6,7

Fig. 1: Etiology of secondary iliopsoas abscesses.

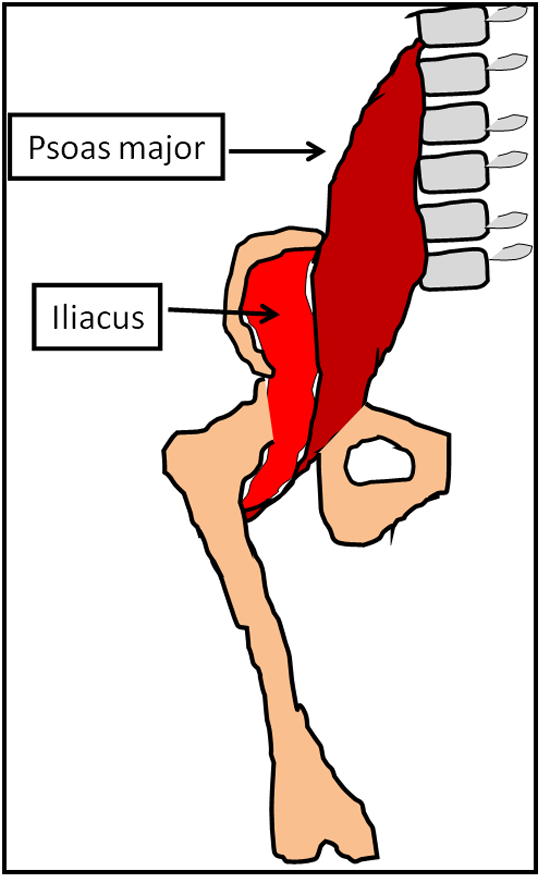

Table 2: Anatomy of the psoas muscle

The iliopsoas muscle forms the posterior relation for the diaphragm, kidneys, renal vessels, ureter, gonadal vessels, and genitofemoral nerve. The sigmoid colon lies in close contact on the left as do the cecum and the appendix on the right. Posterior to the iliopsoas is the quadratus lumborum muscle and the transverse spinous processes. In the thigh, the iliopsoas muscle forms a part of the floor of the femoral triangle.

Fig. 2: Anatomy of the iliopsoas muscle.

Clinical Features

The classic clinical triad consisting of fever, back pain, and a limp, as described by Mynter in 1881,2 is present in only 30%of patients with a psoas

abscess.8 Important symptoms include malaise, anorexia, weight loss, nausea, back/flank pain, abdominal pain, limp, and groin lump.8

Important clinical signs are antalgic gait, flexed and externally rotated attitude of affected lower limb, and a tender/nontender mass palpable in the

lumbar fossa or distally in the proximal thigh. An important test is to elicit the psoas sign where there is pain on extension and internal rotation

of the ipsilateral hip. The sensitivity and specificity of the psoas sign have been reported to be 16% and 95%, respectively9 (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Psoas sign.

Investigations

Routine laboratory investigations including full blood count, C-reactive protein level, and ESR are useful in confirming the diagnosis of an inflammatory mass. Blood culture may be useful in identifying septicemia.

Ultrasonography can be used as a diagnostic and therapeutic modality by performing a USG-guided aspiration. CT scan offers the similar advantage of a

guided aspiration and drainage of the abscess.

However, MRI is more sensitive than CT scan and delineates the abscess with more accuracy and defines the inflammatory changes within and beyond the

lesion efficiently.10,11

Treatment Guidelines

Traditionally, surgical drainage was the treatment of choice.12 It has since been established that image-guided percutaneous drainage is a very

effective and safe alternative.13 CT-guided percutaneous drainage is the initial procedure of choice, with successful decompression seen in at least

50% of cases, with up to 100% success after a second drainage14,15 (see Fig. 4). Technical difficulties with CT-guided drainage are encountered in

cases of small abscesses, multiple septae within the abscess, and inaccessible location.14,18 USG-guided aspiration followed by drainage of the abscess

with a pigtail catheter is an alternative to CT-guided drainage.

The indications for open drainage are as follows:

- Associated abdominal pathology such as Crohn disease or diverticulitis16,17

- For large, complex, and multiloculated abscesses

- If imaging shows gross involvement of adjacent structures

- When percutaneous drainage fails

Small abscesses up to 60 mm may be managed without aspiration by administering broad-spectrum antibiotics that cover S. aureus and any other possible

causes of IPA.4,9,12,13,16–18 However, the success rate with antibiotics alone is only 20%.14

Fig. 4: Computed tomography-guided biopsy/drainage.

|